Hi All,

I created this document with input from Professor Steve Rauch, Terry (Burd) and a number of other people on mvertigo who reviewed this work. It combines information from the science literature, from neurologists and other specialists, and a great deal of the knowledge that we have gained through our own personal experiences here on the forum.

Vestibular Migraine Survival Guide 2014

This guide outlines how to identify, “survive” and handle chronic migrainous vertigo, otherwise known as vestibular migraine (VM) or migraine associated vertigo (MAV).

Migraine is NOT just a bad headache but “a global disturbance of sensory signal processing“. In other words, sensory information – sensations – are distorted and/or intensified. Moreover, some people have a form of migraine that NEVER involves headaches and presents as only non-pain symptoms. If we examine the statistics, migraine affects approximately 12% of the population (16% in women and 8% in men) while Meniere’s disease (MM) affects about 0.2% (or about 2 in every 1,000 people). MM is therefore a relatively rare condition although many with VM are frequently misdiagnosed with MM. When you consider that the second most common symptom of migraine after headache is dizziness, it stands to reason that migraine should seriously be considered in cases of chronic or sporadic unexplained dizziness and vertigo, especially where there is no unilateral (one-sided) fluctuating, progressive hearing loss in the lower ranges. Note, however, that approximately 20-30% of patients with migraine headache exhibit VM. About 20% of VM patients develop hearing loss on one side – evidence of “endorgan damage” in the cochlea. Those patients with VM who mimic Meniere’s syndrome – episodic vertigo lasting 20 min - 24 h plus hearing loss – nearly all gradually develop evidence of endorgan damage (a.k.a. “vestibular hypofunction”).

As most of you who have searched for answers will know, there is a huge amount of misinformation and myth about migraine on the internet, from regular doctors, and even some specialists. Worse still, some end up going from doctor to doctor for years never knowing that migraine is the root cause of their dizziness or that it is greatly exacerbating their Meniere’s disease. Conversely, some are given a correct diagnosis but refuse to accept that they are a migraineur despite evidence to the contrary (they are convinced that migraine must produce severe headaches or that migraine could not possibly be the root cause of debilitating dizziness and other frightening neurological symptoms). Still others don’t realise or won’t accept that other illnesses can act as complicating cofactors triggering their migraine brains.

There is currently no cure for migraine, which is a genetic disorder, and so there is a huge range of medications and treatments (sometimes expensive, misleading and completely ineffective) on the market to choose from. Knowing where to begin in tackling this can seem like climbing a mountain at first glance. Who do you believe and what drug or treatment do you try? The great news is that we do know through science-based medicine (supported by people’s personal experiences here), that there are some very good ways to fully manage this condition that work. In almost all cases, a person with migraine can rein it in and lead a normal life once they know what they’re dealing with and how to handle it. It took both Terry and I about 3 years to finally work out that migraine was the root problem we were dealing with. We know the frustration, fear, and suffering that it brings in not knowing what is going on and feel very strongly about making this information freely available to other people in hopes that they will avoid the long and winding road in understanding what has happened. In short, we hope this will be a “Vestibular Migraine Survival Guide” that people can use to navigate their way out of the migraine abyss.

Presentation

A person with VM may present in several ways. Someone who has migraine with aura (visual symptoms, numbness or tingling, motor dysfunction) will typically report distinct vertigo attacks, usually lasting minutes to hours associated with nausea that can occur before, during, or after the onset of dizziness. They describe feeling very tired and are very sensitive to light (photophobia). Sensitivity to sound, tinnitus and some hearing impairment may occur. This hearing problem can suggest MM but in the case of VM it typically, but not always, occurs bilaterally (in both ears). Tinnitus is often high-pitched or a roaring within the head whereas in classic MM, it is usually low-pitched and in one ear only. Towards the end of these symptoms, the patient will likely develop a headache or a feeling of pressure in the head. After sleeping several hours, they awaken symptom free. This form of attack is difficult to distinguish from MM; indeed, large studies have shown that 25% to 35% of migraineurs experience episodes of dizziness or vertigo, many of which are indistinguishable from Meniere’s attacks.

A more common type of VM and difficult to diagnose is when there are less distinct episodes of vertigo or there is no headache at all. Approximately 50% of vertigo attacks related to migraine occur in headache-free periods. Furthermore, migraine dizziness is often felt as chronic dysequilibrium (the feeling you have walking down the street after too many glasses of wine), lightheadedness, a swimming drunk feeling, floating, or a feeling of being disconnected from the world (also called derealisation). Often a “brain fog” descends and thought processes become more difficult and slower. It may become harder to concentrate and absorb information or follow a conversation. Short term memory may suffer as you struggle to remember words or a person’s name. Feelings of dizziness and vertigo can worsen when you change your posture; however, it differs markedly from BPPV. Nystagmus (eyes pulsing in a particular direction) may also be present with a postural change with VM.

Triggers

People with MAV will often note attacks that are set off by visual stimulation (visual vertigo) or motion. They have difficulties in stores with long aisles and hate fluorescent, flickering or bright lights. Stripes and bold shimmering patterns can also be problematic. For some people, walking outside on a bright sunny day will cause dizziness and a feeling of surrealism requiring dark sunglasses or special contact lenses to stop the effect. Watching a train pass, watching your fingers typing on a keyboard, scrolling movie credits or watching a video game on a computer may provoke dizziness. Even crowds can be a problem. Some are temperature sensitive such that a shower or a cold wind on the head may precipitate a headache or dizziness. Repetitive tasks such as long hours on a computer, or even gardening may set off a person with VM. Around 50% of migraineurs have a history of feeling car sick, became easily sea-sick, or they avoided amusement park rides as children. These problems often lessened or went away when they became an adult but reappeared with the onset of VM.

Other triggers include hormonal changes, stress, inconsistent sleep routine (too much, too little, or interrupted), weather changes, certain smells, loud repetitive noises, exercise and travel. Fragrances and certain smells that can trigger attacks include: perfumes, scented personal care items, laundry detergent smells, scented cleaners, out gassing of new materials (plastics, building materials, car interiors) and smoke of any kind. For those with allergies, dust, dust mite, animal dander or mould may also be a trigger. Attacks tend to cluster around holidays due to the stress (both good and bad stress) of new activities, travel itself (jet lag and sitting in a pressurised jet cabin) and dietary changes – most notably from foods like red wine, chocolate, aged cheeses, and smoked meats. Attacks often occur after periods of intense stress (letdown migraine) such as moving house, starting a new job, relationship break down or from dealing with the hospitalisation of a family member. Extended travel by car, especially as a passenger – or for some as the driver – is very stimulating and can be more problematic than flying in a jet. Boat trips and cruises or just playing in waves at the beach can also set off attacks. A migraineur’s list of triggers may be quite long. Some of them, such as lack of sleep, may always lead to a migraine attack while for others, it may take a combination of several triggers to bring on an attack.

Patients with VM will typically show depressed mood, heightened anxiety, or mood instability. Many of these people will have seen a psychiatrist, psychologist, or therapist and will often describe themselves as having an “anxious” personality. Some may have a history of depression and/or panic disorder. It’s not uncommon for a patient to be told by a doctor, “you’re just anxious” on examination and that their dizziness is due solely to anxiety or depression. What they do not realise is that more than 50% of patients with vestibular migraine have comorbid psychiatric disorders (see Vestibular Migraine Diagnostic Criteria, 2012).

Finally, it can often be found that the first attack is the most severe and of greater intensity and duration than those that follow. Sometimes the initial attack is consistent with vestibular neuritis (VN) followed by a long compensation period. Under normal circumstances an acute attack of VN will last anywhere from 2 days to 6 weeks followed by a period of chronic compensation. Vestibular rehabilitation therapy (VRT) may be necessary and the patient will usually recover completely. In a susceptible migraineur, however, an attack of VN or other viral illnesses such as Bell’s Palsy can be the “Big Bang” that initiates the chronic migrainous vertigo state with no end in sight. The patient may think they are still suffering from VN or labyrinthitis long after it has resolved, but it is migraine that perpetuates their dizziness and keeps them feeling ill. VM patients are also highly susceptible to BPPV (loose ear crystals moving around in the inner ear canals) occurring at a rate 3X greater than any other idiopathic (unknown) cause. A BPPV attack may either provoke the onset of chronic migrainous vertigo or occur sometime after the first migraine episode.

Chronic Migraine

It is important to note that many do not realise that migraine can be a chronic condition – that is, there are symptoms that come and go on a continuous basis throughout the weeks and months with a constant background of low-level vestibular and other neurological symptoms. Sometimes they spike and you will have horrendous symptoms for days or weeks and other times you may be much more dizzy than usual for days and then have it tone down again – “back to baseline” as we say. Others are constantly dizzy and feel a persistent rocking sensation or a feeling as though the room is always tilting. The ground may feel like sponge and a person will feel as though they are “bouncing” as they walk. Other common chronic symptoms include neck and shoulder pain, back pain, sinus and face pain, chronic fatigue and symptoms that are misdiagnosed as fibromyalgia. Some experience the headaches of migraine as “tension-type” headaches (TTH) as defined by the IHS. According to some neurologists, TTH should never cause debilitating pain or light sensitivity and those that do are in fact experiencing migraine. Others will feel flu-like symptoms for days but it is not the flu. Chronic migraine also typically causes sleep disruption with such a person waking many times during the night. They may wake feeling unrested, anxious, and run down.

Note that migraine produces neck pain in a great many sufferers – sometimes referred to as a “coat hanger” headache that may also involve pain in the trapezius muscle across the shoulders. Pain from the neck refers pain to the head and the back of the eyes again causing confusion about its origin. This can be very misleading because a migraineur with neck pain may think that neck pathology is the root cause behind their dizziness and ill feelings. While it is not the root cause, if repeated attacks of neck pain occur (called “migraine neckache”), trigger points can form in the neck setting up a chronic state of pain and dysequilibrium. Trigger points are tight balls of tensed muscle or muscle spasm that are very painful to the touch. The muscle spasm inhibits proper movement of spinal processes beneath it in the neck further adding to the pain and may also produce significant nerve irritation. Taken together, and left untreated, this all acts as a potential chronic migraine trigger. And so a nasty situation is set up where migraine continues to cause neck pain and resultant trigger points and stiff neck joints triggers further migraine attacks. If you feel this is a problem for you, seek out the advice and treatment from a qualified physiotherapist/ physical therapist. This type of problem usually responds to treatment very quickly.

Treatment

The good news is that migraine can be reined in and a high percentage of people can stop the symptoms and resume a normal life. So what do you do if these horrible symptoms have descended into your life? Identifying and avoiding triggers is probably the single most powerful thing you can do to alleviate the symptoms of migraine and is half the battle. Remember, a “migraine brain” is super high maintenance and hypersensitive – like a diva or a thoroughbred race horse. It wants everything to stay the same and wants to be treated like royalty. Throw anything new at it or upset the balance with a trigger and it can/will react angrily and a migraineur will pay the price. In this order, and according to scientific evidence and from those who have gained control of this illness, these are the steps you should follow:

A. Lifestyle Modifications

The migraine lifestyle and diet includes three parts. By following these steps, around 40% of migraineurs achieve excellent results and symptoms resolve.

(1) Regular schedule – every day should look like every other day. You should eat regular healthy meals and never skip one. Make sure you keep a regular sleeping pattern EVERY day, going to bed at the exact same time every night and allowing for about 8–9 hours of sleep. You should get regular daily exercise even if it’s just a walk to the end of the block and back again. Ideally you should aim for 30 minutes of aerobic exercise. Because more vigorous or intense exercise can itself be a trigger, you may need to start off very slowly increasing it incrementally over time until it is a daily activity and does not trigger attacks. Drink about 2–3 litres (about 8–12 cups) of water daily if you can; a migraine brain must stay well-hydrated.

(2) General medical “tune-up” – migraine symptoms are more likely to flare if there are other medical/physiological stresses on your system. Migraineurs should work with their other medical professionals if necessary to get control of other health problems such as allergies, food intolerance, thyroid, blood pressure, blood glucose, and hormone problems, or any other obvious vitamin/ mineral deficiencies. Colds, the flu, and other viral infections are notorious for triggering nasty attacks and so good personal hygiene is key to reducing risk of infection (e.g. wash your hands often and avoid touching your eyes, nose, or mouth during flu season).

(3) A migraine diet – there are many foods that are potential migraine triggers. The simple way to remember a migraine diet is to eat ONLY fresh foods. When in the supermarket it usually means not buying anything in the aisles but shopping around the perimeter. You can eat fruits (though citrus and bananas might be a trigger for some), vegetables or meats. Stick to unprocessed low glycemic index carbohydrates. It’s best to cook your own food and prepare all foods fresh when you want them. If you do this, you are on the migraine diet. The list of “Thou Shalt Nots” is long and not great. Here is a sample of the MAIN triggers:

• nothing aged, cured, pickled, or fermented (cheese, beer, wine, alcohol, vinegar, soy sauce, yoghurt, sour cream)

• no caffeine (coffee, tea, chocolate, colas)

• no artificial sweeteners/sugar substitutes (especially aspartame)

• no nitrites (deli meats – proscutto, pepperoni, salami, etc)

• no sulfites (red wine, dried fruits – raisins, apricots, etc)

• no nuts

• no MSG (monosodium glutamate – take-out Asian foods (e.g. Chinese, Thai), and virtually every packaged food in the grocery store – usually listed as “natural flavour additives,” not MSG, in the ingredients label). In Australia, MSG is labelled as number 621 on the ingredients list. For more information on MSG labelling, see this document:

http://www.truthinlabeling.org/hiddensources_printable.pdf

In order to determine if migraine is the problem, a person must be willing and determined to make a concerted effort to identify triggers. Note that triggers do not cause migraine, but ignite it, like putting a match to dry kindling and so identifying them is critical. For example, keeping an ongoing diary of daily symptoms and recording all possible triggers is a great way to find patterns and isolate them. Others may need to use an elimination diet to isolate food triggers. Whatever the method, some may only do so half-heartedly with no definitive results to work with and will thus incorrectly rule out migraine. Accurate and useful results require putting in some time and effort.

IMPORTANT

Dr Nicholas Silver in the UK is the neurologist migraineurs see when they have failed to gain migraine control under the supervision of previous neurologists. He is extremely systematic and methodical in helping people gain control. He says the main reasons that people fail – even when they are on a migraine preventive drug – is because patients are still using caffeine in some form (coffee, tea, green tea, chocolate, colas) or they are using painkillers. Some nasal decongestants can act similarly to perpetuate the condition. A chronic migraineur should NEVER use any painkillers – not ibuprofen, paracetamol, Tylenol, or aspirin and definitely not the more heavy-duty ones such as the opiates unless it is an emergency but no more than four times per year. Even one cup of caffeinated tea per week can be enough to perpetuate chronic migraine, so NO CAFFEINE. If you’re using painkillers now, the best way to get off is to go “cold turkey”. Headaches may get worse over the first week and should then ease off. Use other methods to work with headaches such as cold packs etc.

If the migraine lifestyle above is followed and you can pinpoint your triggers and develop a firm foundation and stick with it, then 40% will see their symptoms resolve and you may only deal with the odd flare-up here and there. For the other 60%, a preventative migraine medication is needed. The author can personally attest to the nightmare painkiller (aspirin) overuse can bring.

B. Migraine medications and evidence-based treatments

There are currently several FDA (or equivalent)-approved evidence-based medications and nearly 100 off-label medications commonly used for migraine prevention. Abortive medications (e.g. triptans) are not known to be of much use to someone who suffers with MAV and may actually perpetuate the problem and so a preventative medication is used. According to Drs Nicholas Silver (who prefers medications that encourage a proper sleep cycle) and Steve Rauch, migraine medications should be started at very low doses and increased slowly over weeks or months until the headache and dizziness goes or the recommended tolerated dose is reached. One should not be put off by the label “antidepressant” or “anticonvulsant”. The dose required may be far below what someone with clinical depression or epilepsy would need. Once stable, you remain on the medication for one year and then it may be possible to come off the drug over another 4-month reduction period at which point a migraineur can remain in remission without medication but still following a migraine lifestyle. Others may need to stay on their preventive for many years or for life. Note that migraine medications are NOT a substitute for the above lifestyle modifications but are a supplement to them. When you find an effective preventive medication, however, you will likely be much less vulnerable or susceptible to triggers, including dietary triggers.

Some of the more common classes of medications and treatments are as follows:

• Beta blockers – propranolol, atenolol, metoprolol

• Calcium channel blockers – Verapamil, Flunarizine

• Tricyclic antidepressants – amitriptyline, nortriptyline (Rauch’s favourite), Prothiaden (Halmagyi and Silver’s favourite)

• SSRI/ SNRIs – citalopram (Baloh’s favourite), Effexor (Hain’s favourite), paroxetine, Zoloft, Cymbalta

• Benzodiazepines – most find these very effective, particularly low doses of valium which has both anti-anxiety and anticonvulsant properties. Dr Timothy Hain recommends low-dose clonazepam which avoids dependence.

• Anticonvulsants – Topamax, Neurontin, Lyrica, Depakote

• Natural remedies – magnesium, vitamin B2 (riboflavin), Coenzyme Q10 (These three natural remedies for migraine headache all have shown promising results as effective natural headache remedies in controlled trials)

• Physiotherapy/ neck massage/ trigger point therapy – stiff and knotted neck muscles (trigger points) can act as a migraine trigger (Note: paradoxically, neck massage or body massage can also trigger an attack)

C. Alternative and other treatments

Note that these treatments have very little or no evidence for efficacy beyond personal anecdotes and/or a possible placebo effect. However, they may give some temporary relief or even long-lasting relief.

• Acupuncture

• Chiropractic (beware of the dangers involved with “adjustments”. The author’s sister-in-law received a cracked rib from a recent chiropractic visit)

• Craniosacral therapy

• Meditation and other relaxation techniques

• Biofeedback

• Low carbohydrate diet (not to be confused with a low glycemic index diet)

Scott and Terry

[size=120]Recommended reading materials:[/size]

“The Migraine Brain” by Dr Carolyn Bernstein

“Heal Your Headache” by Dr David Buchholz

The following journal article is one you can print off and take with you when you visit your doctor.

[size=110]Vertigo and migraine – ‘How can it be migraine if I don’t have a headache?’[/size]

MedicineToday 2011; 12(12): 36-43

It’s from Medicine Today, an information source for Australian physicians. The article covers all of the major bases, and is written in language that doctors like. In other words, if you suspect you have VM but have a doctor who you think is not on the same page, then print this off and take it with you to your appointment.

vertigo_and_migraine2011.pdf (697.3 KB)

(Edit by @turnitaround, my best guess is the file above. Old broken link:

http://www.mvertigo.org/articles/vertigo_and_migraine2011.pdf)

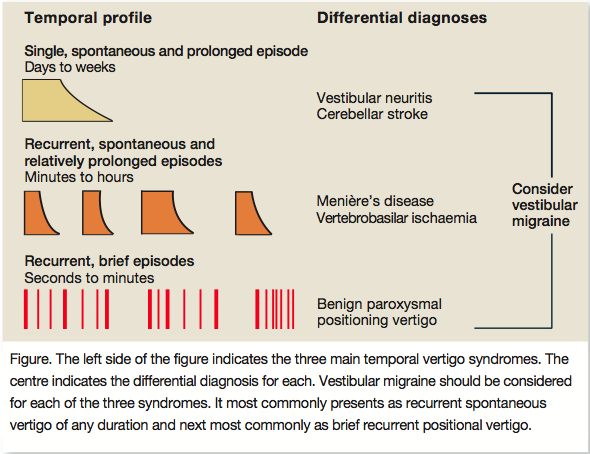

There is a nice little differential diagnosis diagram in it that will help your doctor and you in working out what it is you’re dealing with. The only area the article falls short, in my opinion, is in the use of SSRIs as a suitable first line (medicine) treatment. There isn’t much in the way of hard evidence for SSRIs and VM (clinical trials) which is why it’s not here. For that we rely on expert opinion (Drs Baloh, Newman, and Tusa) and case studies reported on the forum.

(Edit by @turnitaround, my best guess is the picture above. Old broken link:

)

)

This paper is also another one designed for physicians in the US but a very easy read for anyone. Take it with you too:

Dizziness and vertigo: Recognizing vestibular migraine in the primary care setting

Clinician Reviews 2014; 24(6): 38-46

recognising_vestibular_migraine_HART_2014.pdf (807.0 KB)

(Edit by @turnitaround, my best guess is the file above. Old broken link: http://www.mvertigo.org/articles/recognising_vestibular_migraine_HART_2014.pdf)

[size=85]Updated by Scott on 10 June 2014[/size]